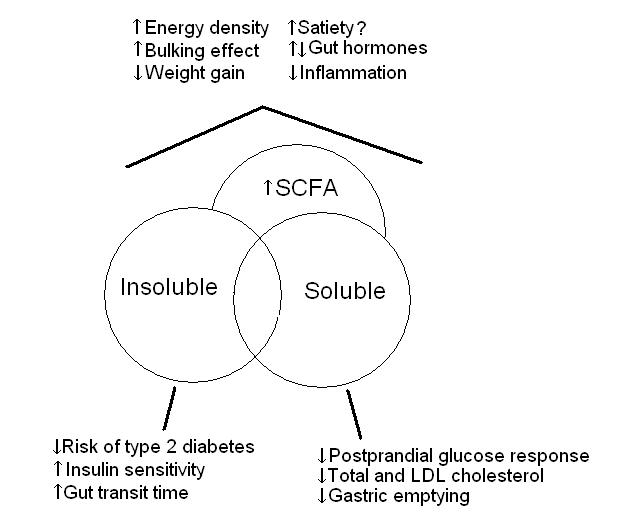

Carbohydrate foods are generally thought of as a source of energy to humans. However, dietary fibre is comprised of indigestible polysaccharide components of plants, and is therefore part of the carbohydrate group of foods. Broadly, dietary fibre can be classified as soluble and insoluble, based on its ability to mix with water in the digestive tract. The health benefits of high fibre diets have been known for some time with research suggesting that dietary fibre is beneficial to a number of conditions including cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes. Separating the benefits of the insoluble fibre component of the diet from the soluble fibre component is difficult because food is a complex mixture of many types of fibre. Recently a number of studies have shed light on the metabolic and digestive effects of fibre and a picture of the benefits is starting to emerge (figure 1).

Figure 1. The health effects of dietary fibre. Short chain fatty acids, SCFA1

The main sources of soluble fibre are fruits, vegetables, oats and barley. However, oats and barley contain insoluble fibre as well as being rich in soluble β-glucans. Dietary fibre is not digested in the upper gut of humans, because the enzymes necessary for hydrolysis of the chemical bonds are absent. However, fermentation of the fibre is possible in the colon, because the microorganisms that inhabit the large intestine are able to use the dietary fibre as a source of energy, in turn producing short chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate and butyrate, which may be absorbed and decrease hepatic glucose output and improve lipid homeostasis. The rates that dietary fibre is fermented varies depending on the fibre present. Soluble fibres such as pectin, inulin and β-glucans, as well as insoluble resistant starch and oligosaccharides are more readily fermented by gut bacteria than cereal fibre such as cellulose and hemicellulose.

Dietary fibre is thought to be beneficial to health as a result of its effect on satiety and subsequently on food intake. Research has shown in a number of cases that high intakes of fibre are able to decrease post meal hunger and increase satiety, although some studies have found no effect. Whether high fibre diets could alter energy intakes over the long term is not so well understood. Observational studies do show that there is a inverse correlation between dietary fibre and body weight, but the effects are small. Dietary fibre is thought to alter the secretions of some gut hormones (cholecystokinin, ghrelin, peptide YY, glucagons-like peptide 1, glucose dependent insulinotrophic polypeptide) that may act as satiety factors, although no effects on hunger or satiety were noted in short term studies.

Some evidence suggests that high intakes of fibre are inversely associated with insulin resistance. Individuals with insulin resistance are more likely to develop diabetes and it has been suggested that dietary fibre may be a useful tool to increase the insulin sensitivity of those in danger of developing diabetes. Dietary fibre may be able to increase the transit time of food through the digestive tract and thus alter the glycaemic index and insulin response to dietary sugars. Dietary fibre may also be able to directly alter inflammation and modulate the immune system (here). Prebiotic fibre such as inulin and oligofructose may bind directly to specific receptors on immune cells and thus modulate immune response. High intakes of dietary fibre has been shown to decrease C-reactive protein in individuals, a marker for systemic inflammation.

RdB